My research lab experience started back in 2017. I applied for a internship program through the University of Delaware wherein I would be assigned to a random research lab on campus for the summer under an engineering professor, and would assist them with their research for that summer. I happened to know the head of the program, Mel Jurist, through my attendance in an engineering summer camp the previous three summers, and she graciously reached out once approved into the program and tried to get me into a lab best suited to me. I am incredibly grateful to Mel Jurist for her reaching out and for putting in the effort to put me into labs that fit me and my interests.

During the summer of 2017, I was an intern in the UD Materials Tribology Laboratory under Dr. David L. Burris. This lab studied the properties of materials, both organic and inorganic, under different strains on a microscopic scale. I was assigned to assist Axel Moore, a graduate student who was working on his PhD at the time, and Jordyn Schrader, an undergraduate student working in the research lab. During my time in the lab, I assisted these two students and Dr. Burris on their research surrounding the rehydration of knee cartilage. The internship program lasted for 7 weeks, but at the end of that time period, I was asked by the members of the lab if I would consider staying and continuing to help out, which I did. This simple gesture by them is something I will forever be grateful for, as I was able to assist them in their work even more for the rest of the summer. I helped Axel Moore finish his PhD and was able to attend his dissertation in which he got his doctorate, while at the same time helping Jordyn Schrader with her summer research. On top of these, my work with Dr. Burris and Axel Moore led to them graciously putting me as a primary author on their research paper regarding the new concept of knee cartilage hydration they were pioneering, which was published in April of 2019. I will be forever in the debt of these three amazing engineers, as they trusted a 16-year-old with their research, their doctorates, and then asked me to continue to work in the lab beyond when I was supposed to leave. Because of their graciousness, I now have the experience of being an actual member of a research lab, not just someone who washes the glassware, and I’ve been able to help with the writing of a research paper from the very beginnings of its creation.

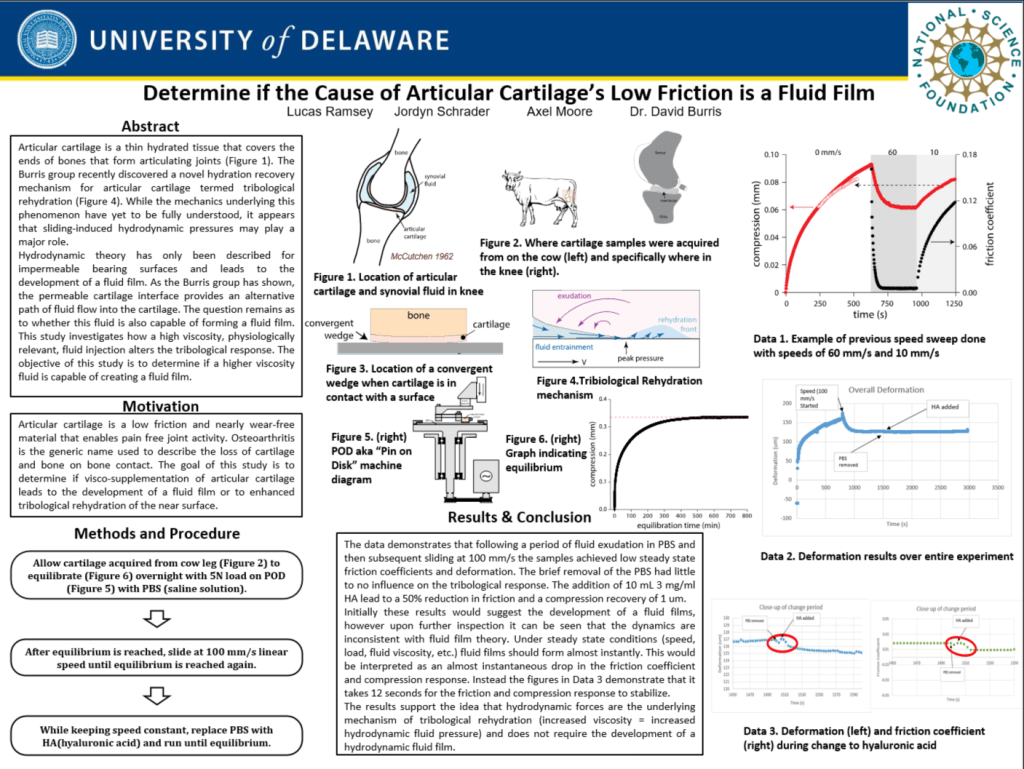

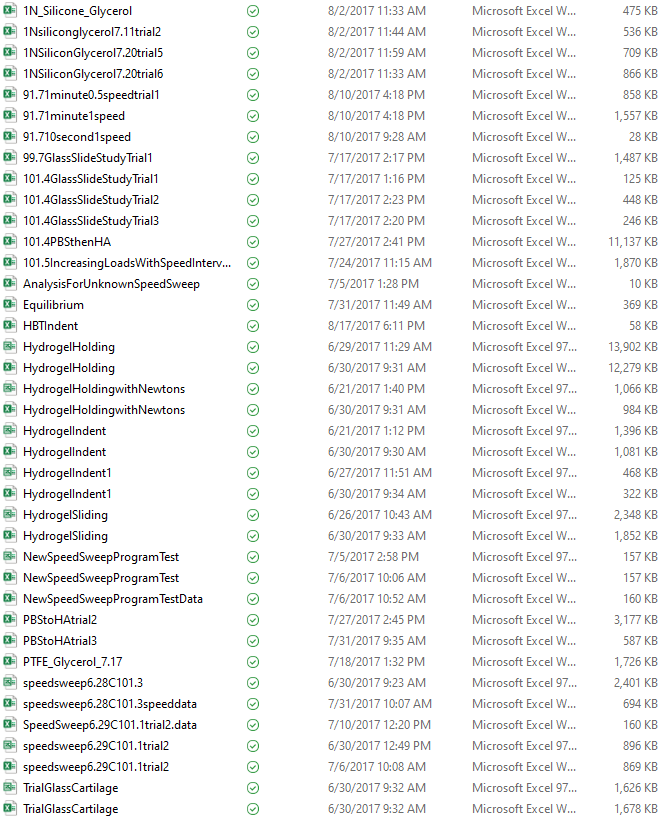

The top left picture is the poster I had to create at the end of my 7 week internship period. I made my poster about the extremely low friction of knee cartilage, how dependent it was on the fluid film, and if the specific fluid on the cartilage impacted the friction coefficient. This was what I chose to write my poster on because it was one of the first things I worked on while in the lab and it helped me understand all the properties of cartilage and the rehydration of cartilage that would later lead to me being as impactful as I was in the lab. The picture on the right is a small portion of the data I assisted in collecting and analyzing, my primary contribution since a lot of the conceptual ideas behind the rehydration of cartilage were beyond my level of education at the time. The bottom left picture is a screenshot of the title of our published paper, which can be found at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11249-019-1158-7.

The following summer, I reapplied for the same internship program. While extremely happy with how much I was able to achieve in the previous research lab, I realized that the biology aspect, while mildly interesting, was not something I wanted to pursue beyond high school. With that knowledge in mind, I focused my application on trying to get into a true mechanical engineering lab if possible. Once again, the wonderful Mel Jurist reached out again and worked with me in order to try and put me in a lab she thought would best fit me. And she could not have been more right. During the summer of 2018, I was assigned to the University of Delaware Information and Decision Science Laboratory. The lab was led by Dr. Andreas Malikopoulos, with multiple graduate students spearheading the research, other graduate and undergraduate students conducting the research, and two other high school interns assisting with the research just like myself. The primary function of this lab was surrounding their scaled city, aptly called the University of Delaware’s Scaled Smart City (UDSSC). (The website for the lab is here: https://sites.udel.edu/ids-lab/)

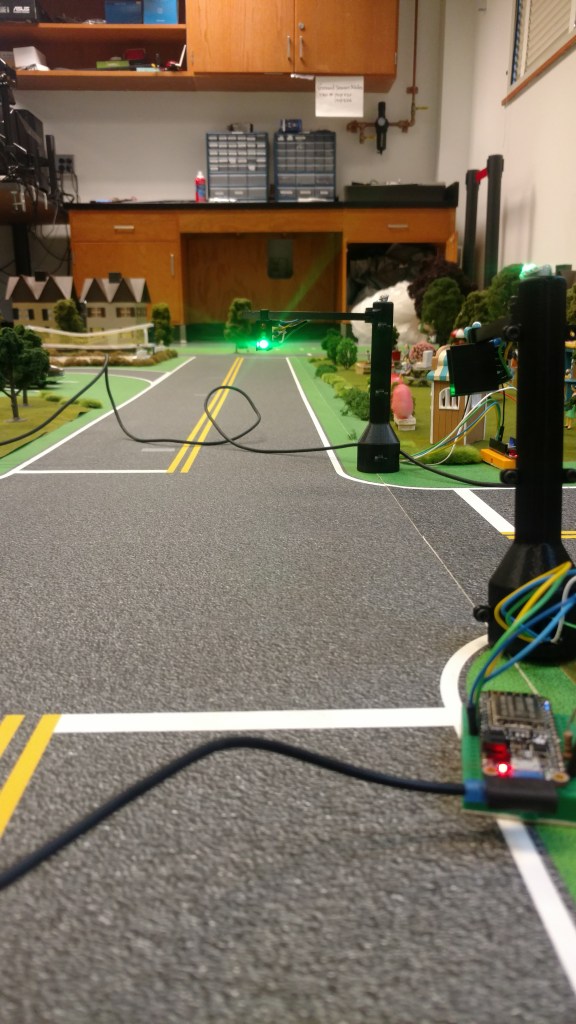

Shown here is the 1:25 scaled city with similarly scaled vehicles. On this scaled city, the lab could easily test full autonomy on a city-wide scale, as well as different levels of autonomous vehicle travel throughout a city. Because of the scaled nature, everything could be easily controlled and manipulated, and was much cheaper than full-size vehicles.

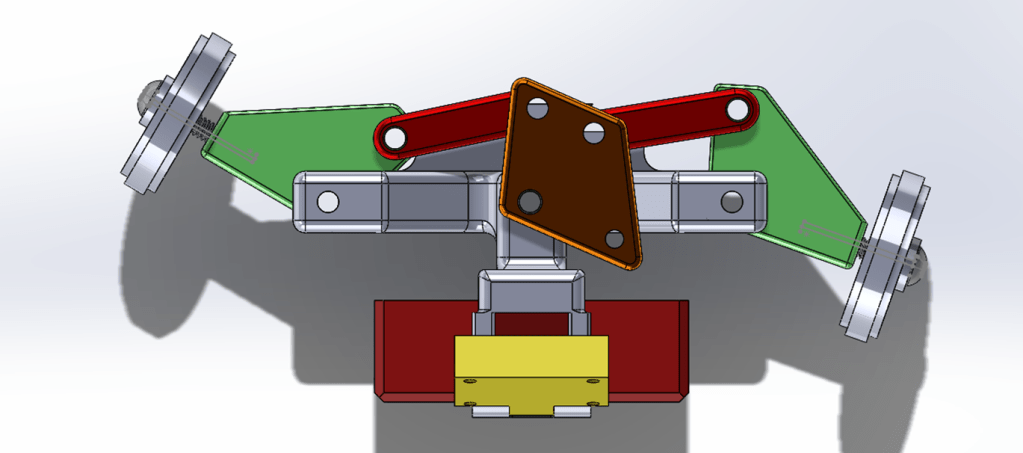

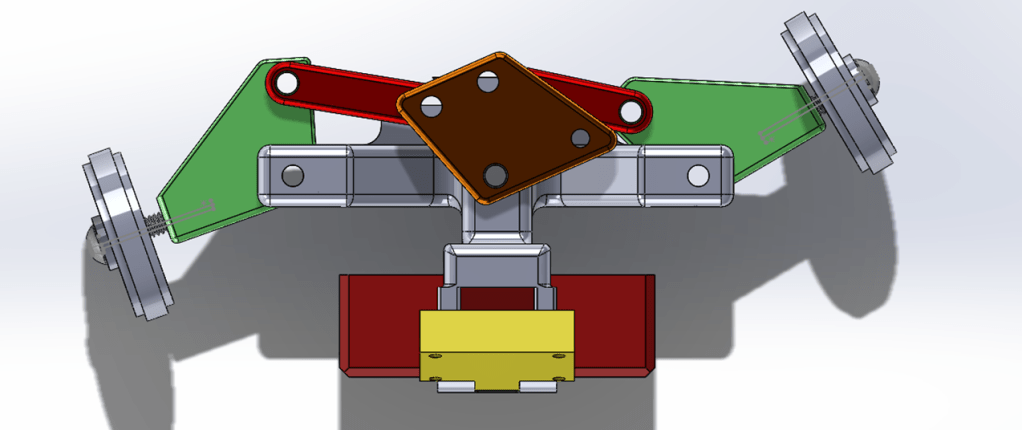

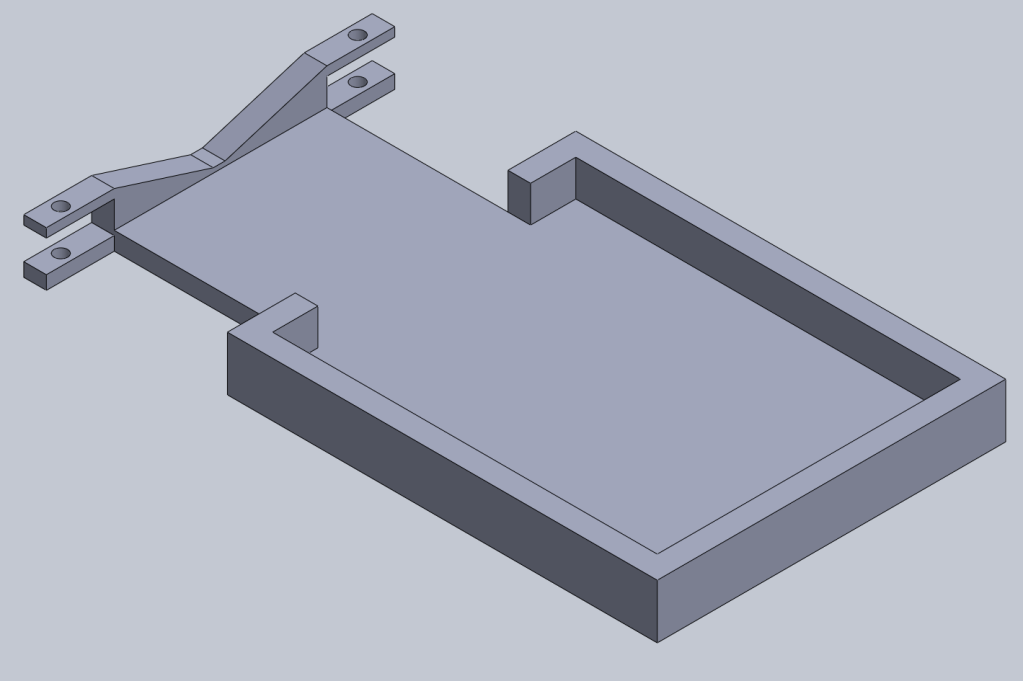

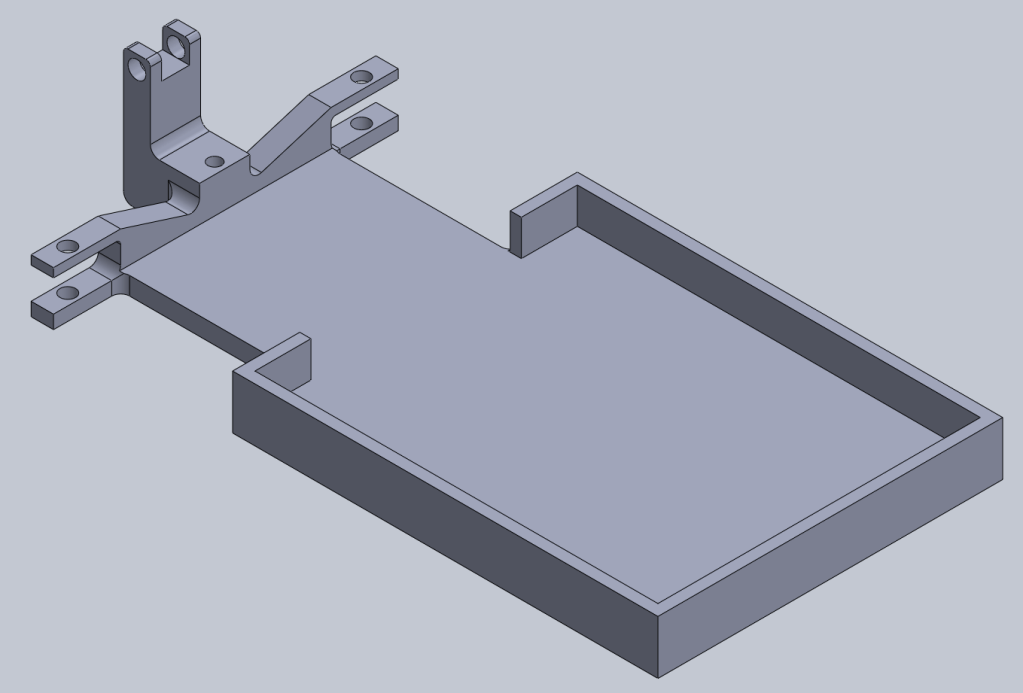

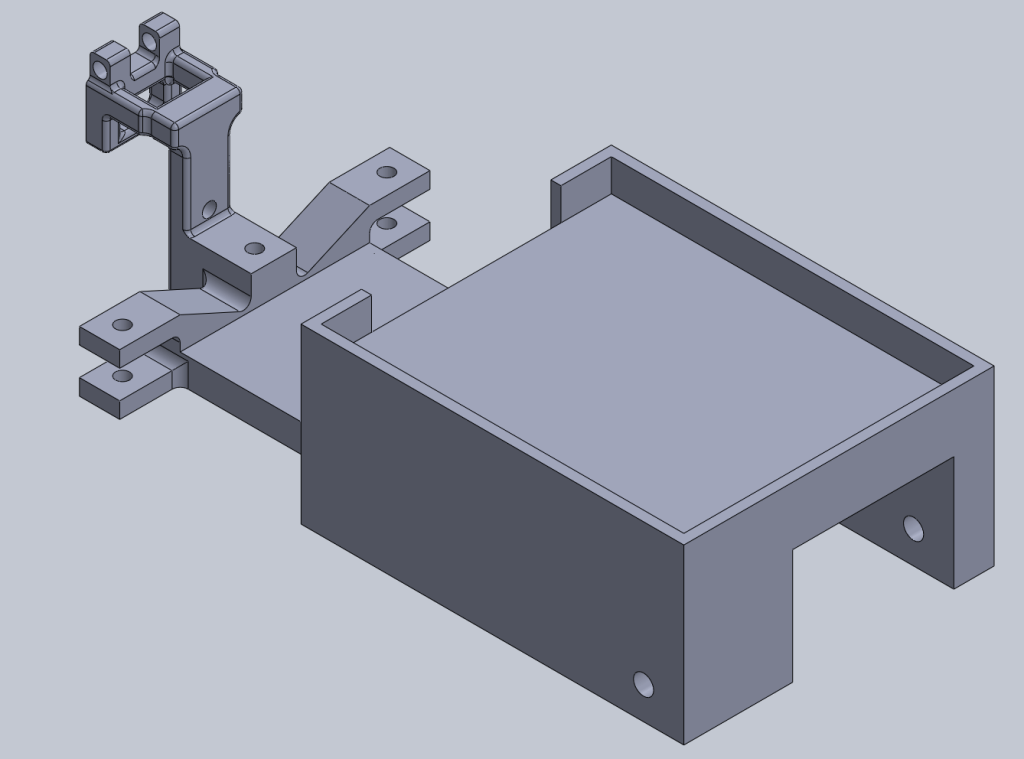

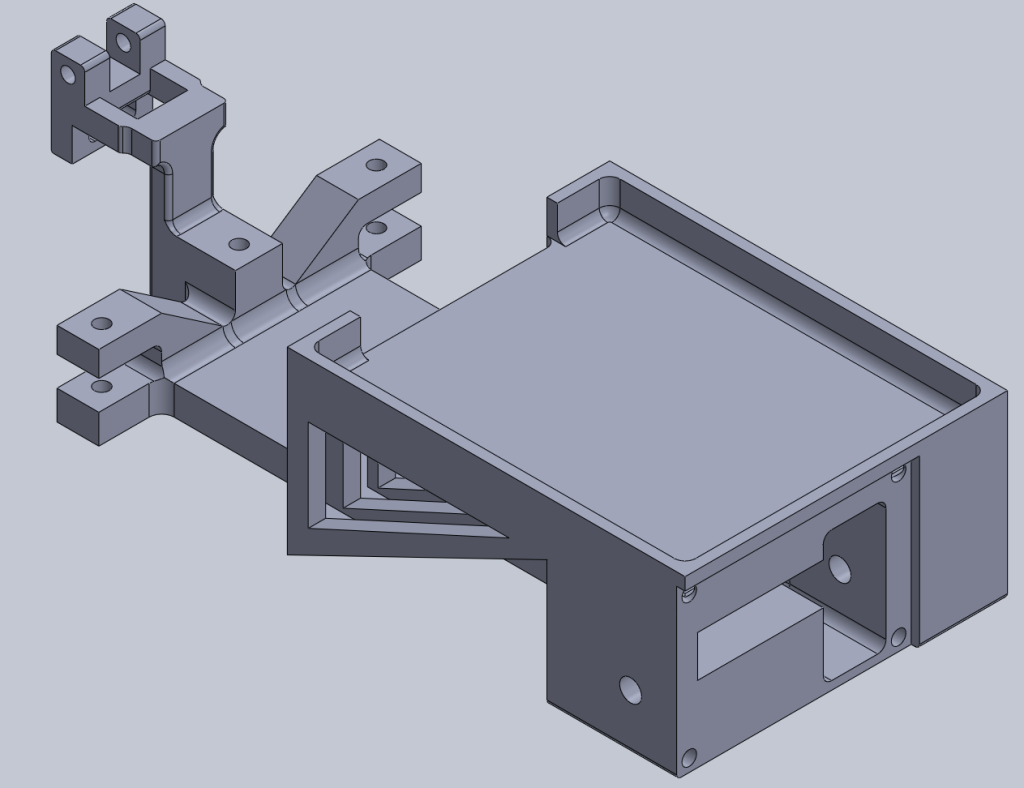

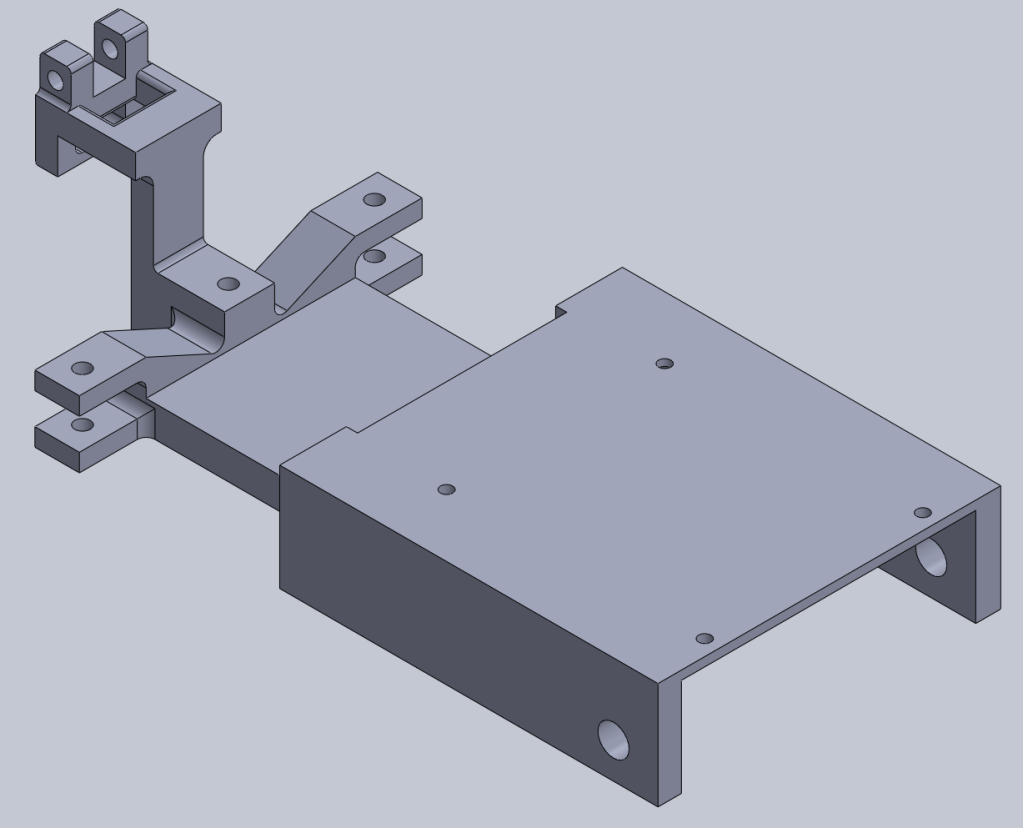

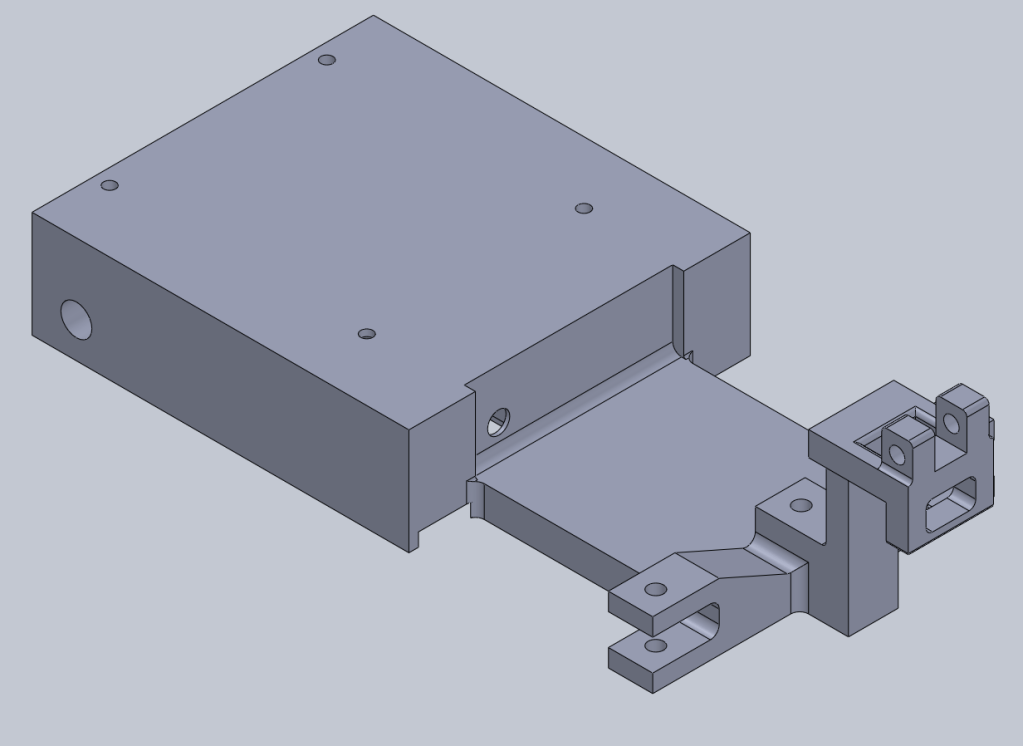

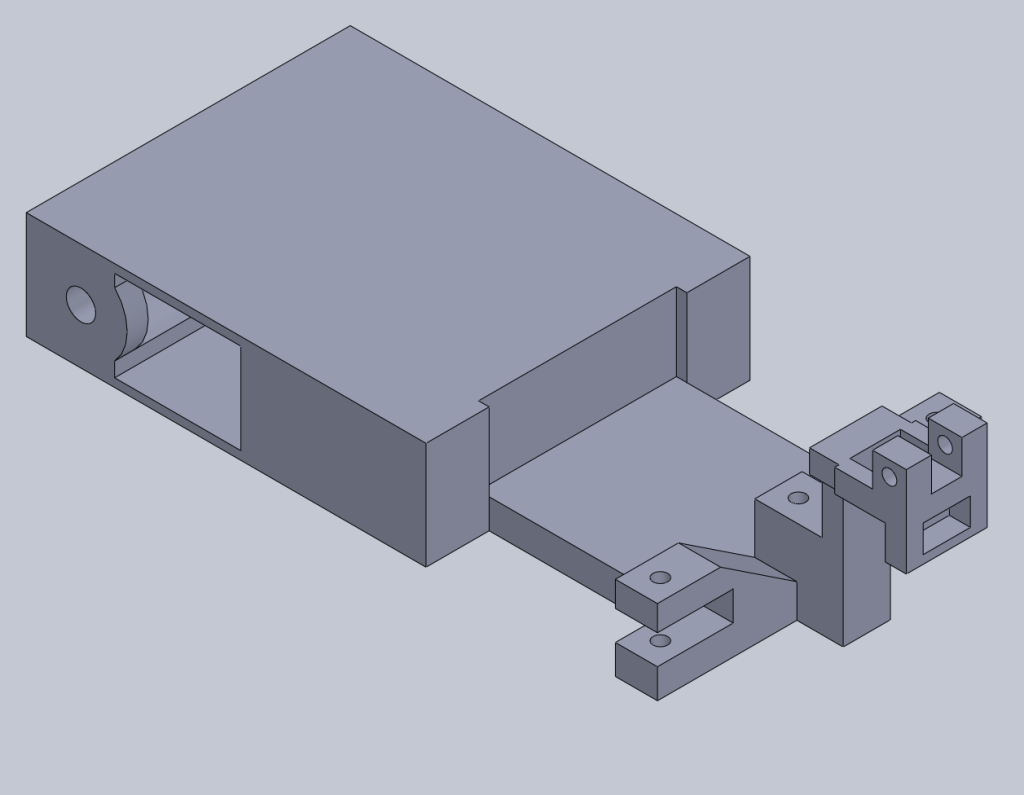

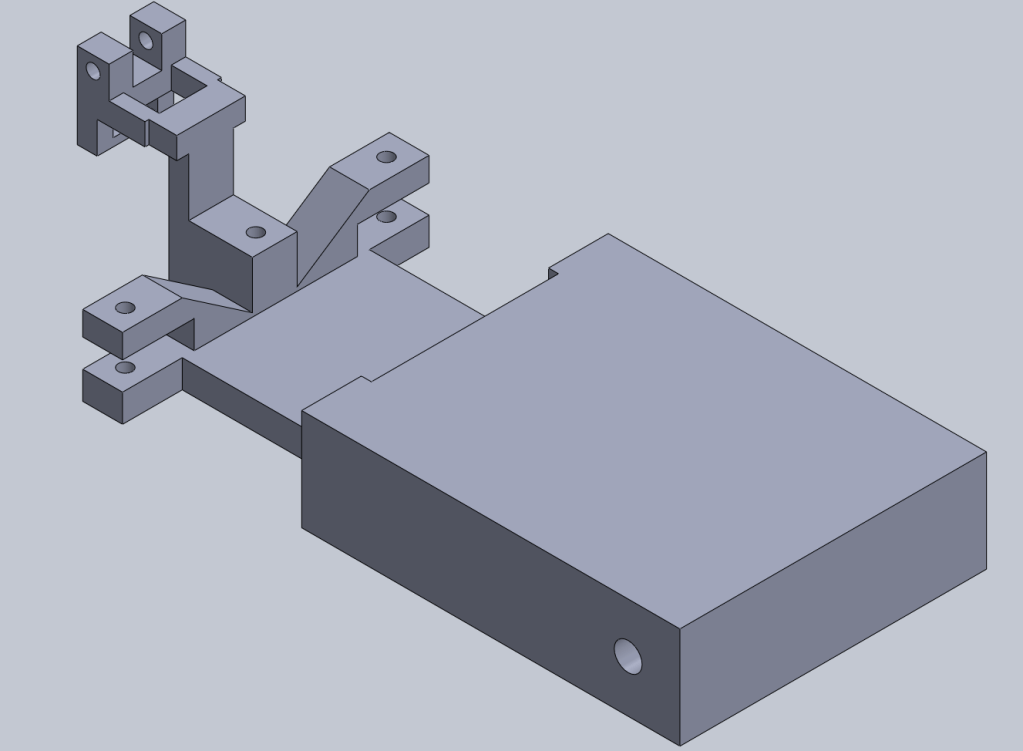

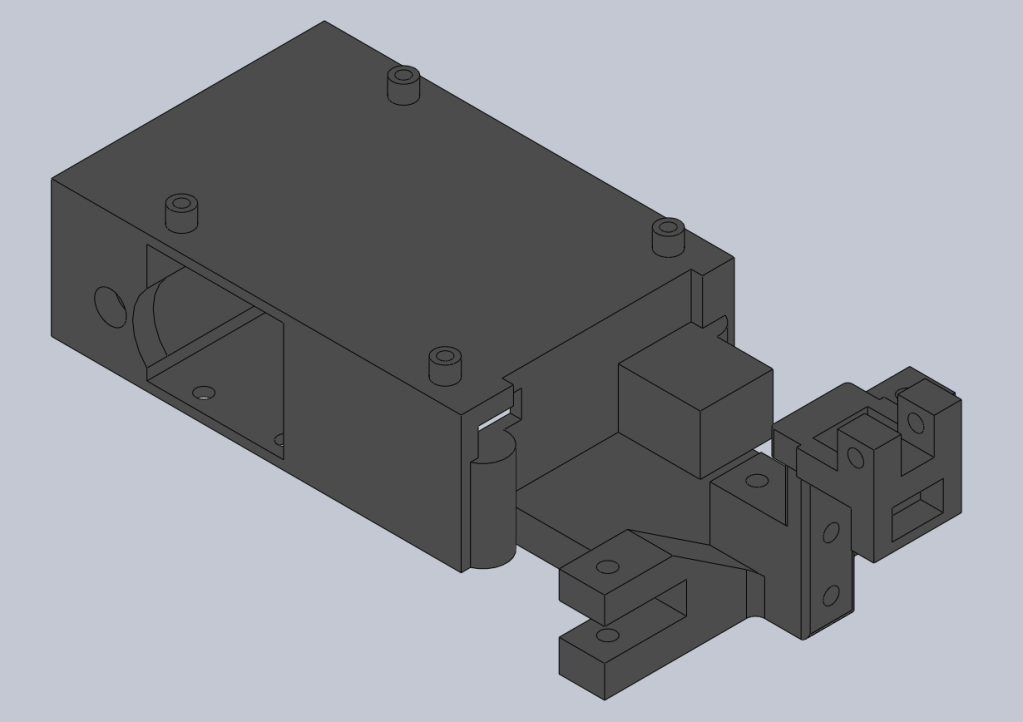

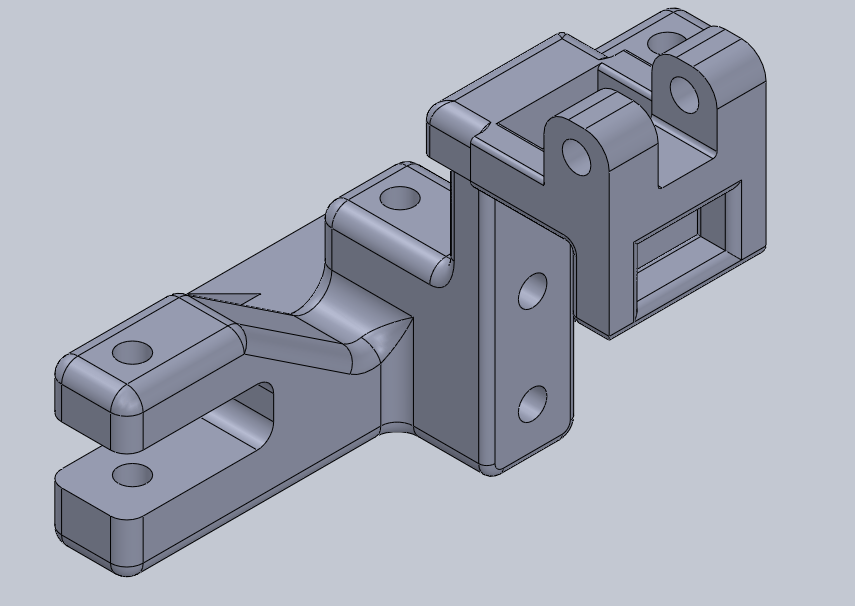

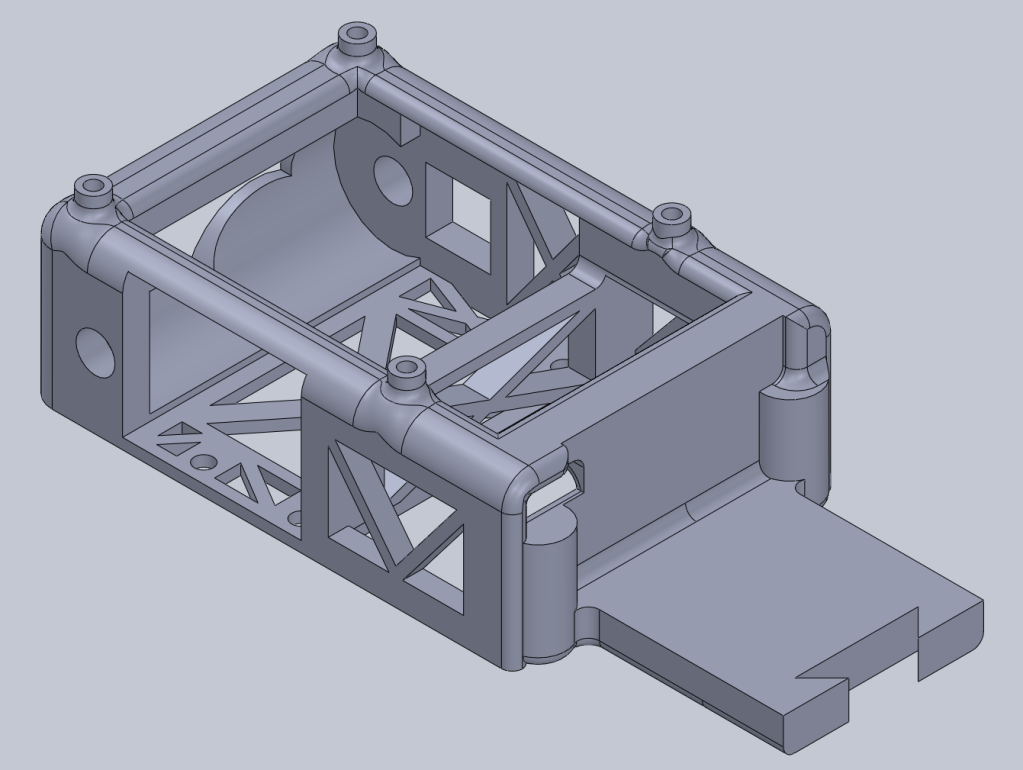

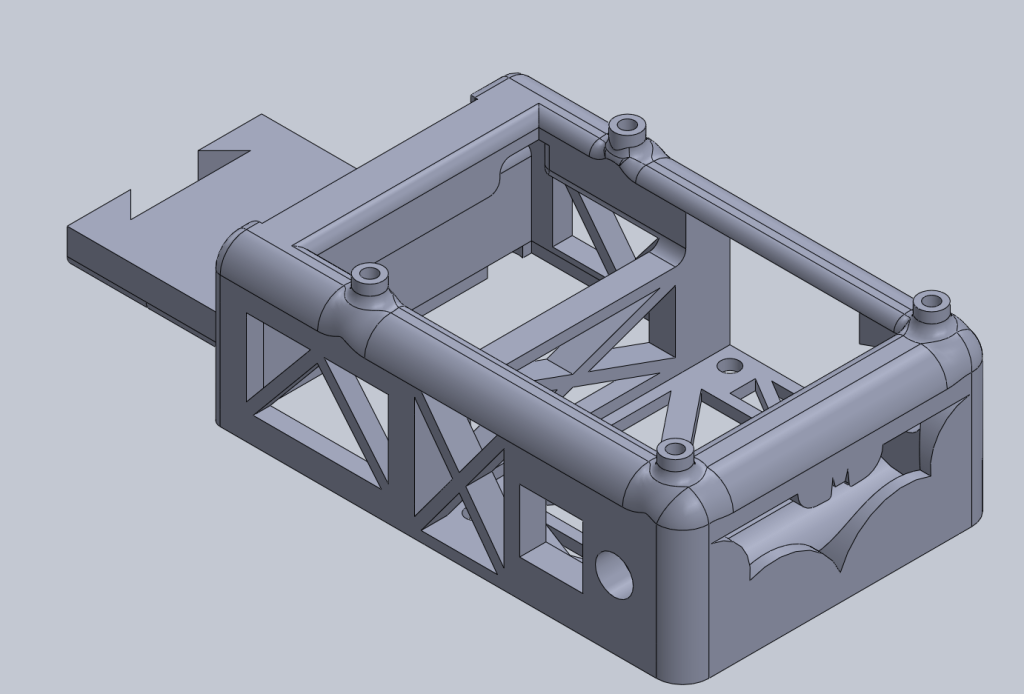

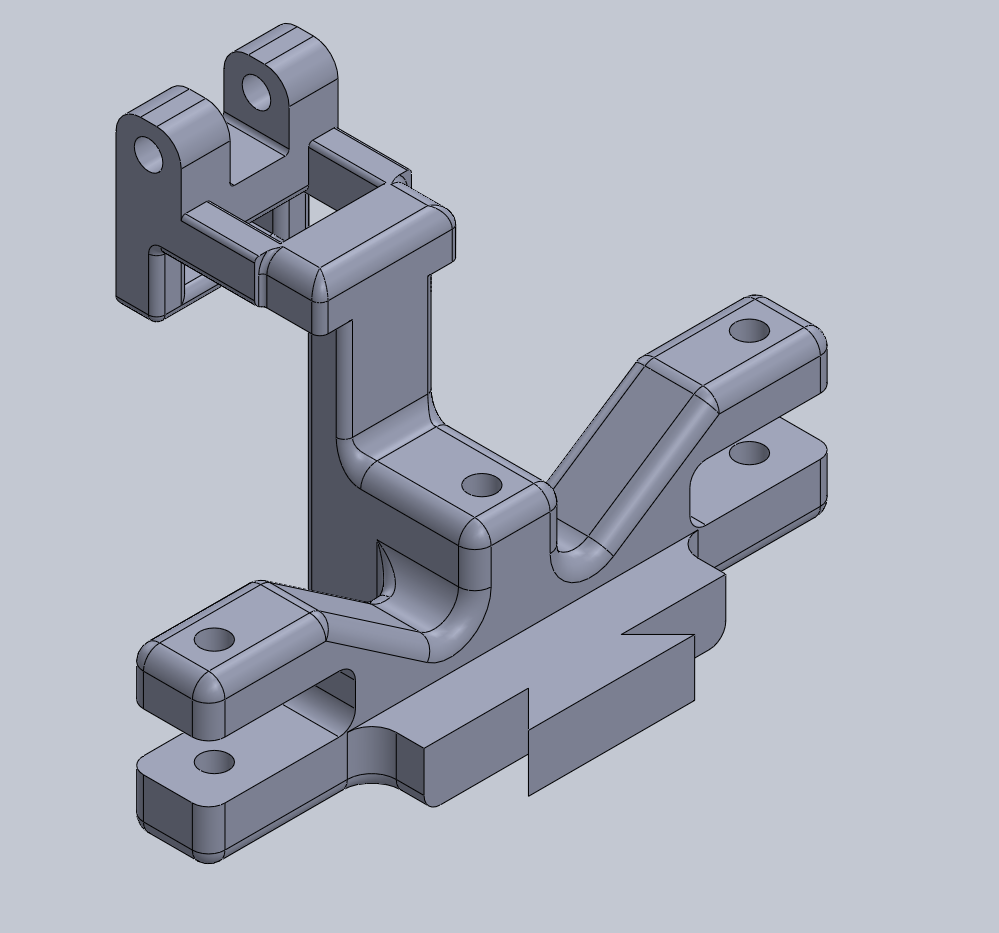

Within my first week at this lab, I was assigned to begin the creation of a new version of the scaled vehicles. They had me start this due to my experience in SolidWorks in the past, and knowing that the undergraduate students who would have been what I was doing weren’t going to start work for another week, they figured it would be better to get a head start. So, I was tasked with making V3 of a 1:25 chassis that could fit various electrical boards, sensors, be battery powered, and would be efficient to make. The first thing I started with was what I assumed would be the hardest: steering. I ended up settling on a double Ackermann style of steering that could be controlled via a central servo, therefore it could be as precise as the lab needed while allowing it to make all the turns through the city. Once the other undergraduate student who was initially tasked with the vehicle redesign, Thomas Patterson, returned to the lab, we began working hand in hand to complete the cars. My main task in the beginning was the steering system I had started, while he began packaging the necessary components, and then I joined him after completing my portion.

Once again, I chose the first project I started in the lab for my final poster presentation. In choosing the steering design for my presentation, it was not only easier to explain than the packaging aspect of the rest of the vehicle design, but was one of the most engineered parts of the car, so I was very eager to show it off.

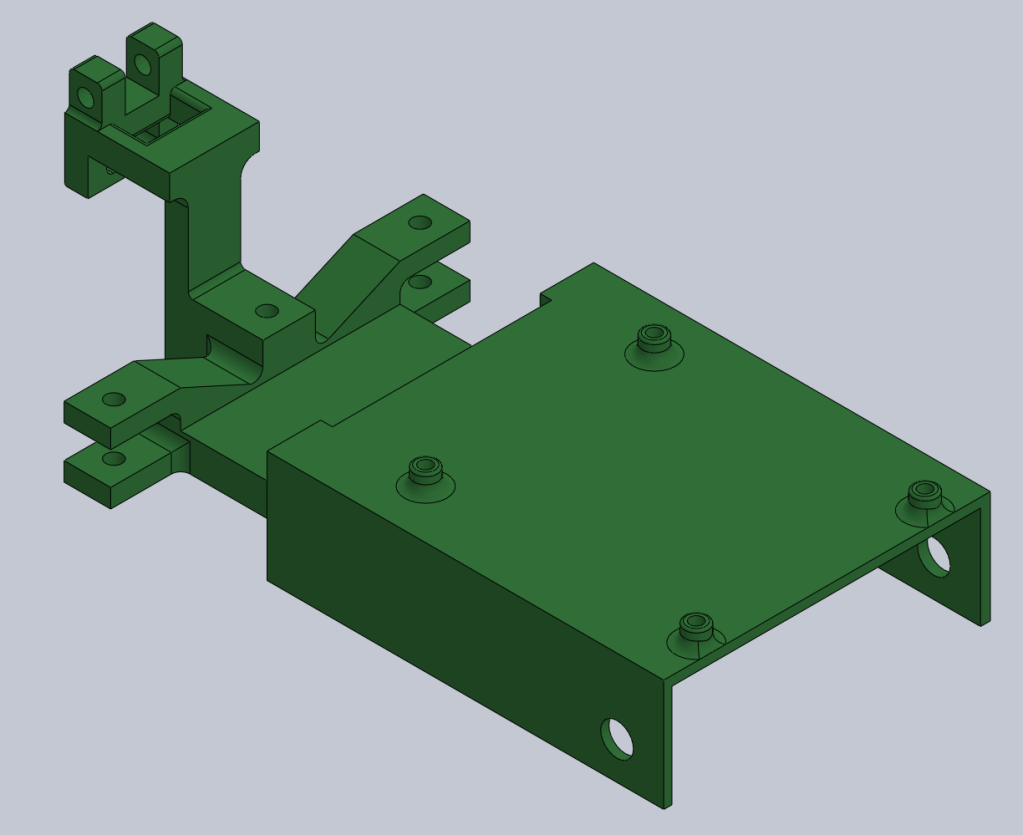

The pictures above show the final design of the steering that I settled on. The central orange piece allowed for a servo to be mounted to the system and steer the car by rotating the orange piece, therefore turning the wheels. Also shown in these images is another request by some of the other students in the lab: the red box houses a sonar box used for distance detection, the yellow plate is for a Raspberry Pi camera used to stay on the road. This was just the front half of the car, we realized part of the way through that while we were only making changes to the rear half of the car, the front was not changing, so we came up with a dovetail design that would allow us to simply fuse the two halves together once complete so we could test it.

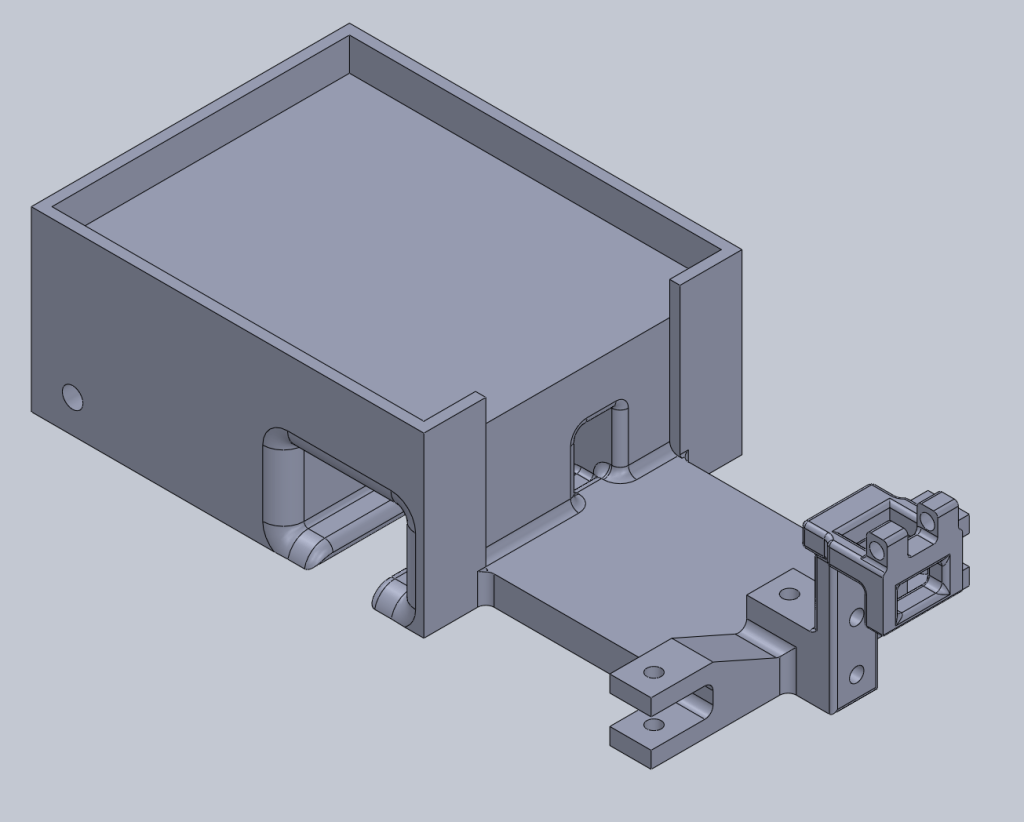

Starting top left, this is the progression of our designs as the summer went on going left-to-right, top-to-bottom in pairs of two in order to show all parts of the design. In the beginning, it started with just the steering and a basic tray to hold anything else. Then I added an extension for the camera mount. The second row shows two different designs I created using a 9 volt battery for power and a small motor. These designs were different mainly in where the battery and motor were in the vehicle. This row is also where I added the sonar box mount and was getting extremely close to completing the steering. The third row begins when the Mr. Patterson and I began working together and during which I completed the steering design. Our first joint task was to create two different designs with motors parallel with the axles and perpendicular to the axles. We did this in order to see which would be a better design overall. The fourth row shows Mr. Patterson’s design with a perpendicular motor in green, and my design with a parallel motor in dark gray. At this point we realized that one of the goals we wanted was to have the motor removable, so we had small motor boxes that would house our motors and could be easily swapped into the vehicles. The very bottom row shows the split of the chassis as mentioned before the images, done for manufacturing and testing efficiency. The left two pictures are the front half that would hold the steering design as well as the sonar box and camera. The rightmost two pictures are my final design for the chassis with weight reductions (yes, that is a Batman symbol on the back, I needed to cut a hole out of the back and instead of just more triangles, I tried to make it interesting). This was one of the final things I did at the lab. As with the last lab, Dr. Malikopoulos and the graduate students running the lab asked me if I wanted to stay longer than the 7 week internship period, and I graciously accepted, continuing the work on the car redesign. I was not able to continue past the end of the summer due to returning to high school, but it worked out because the vehicle redesigns were picked up as a senior design project by the university. And since I was a principle creator in where the designs were at the time of the senior design project beginning, I was pivotal in easing the transition from one high school student and one undergraduate creating the car to now five undergraduate students taking over our work. The amount of trust that was put in me to not only start this project but to be one of its heads even when Thomas was present, and not to demote me underneath him, that level of trust in me was and is something that I cannot put into words how much I appreciate. It allowed me to further grow my understanding in packaging and the design process, and those are things I took with me and still continue to build on to this day.

Due to my knowledge of 3D design, my very basic understanding of electronics (which at the time encompassed basic circuits but with lots of experience soldering), and a very minimal ability to code, I was able to help another undergraduate student, Arnav Prasad, begin to make traffic lights. We designed these to be free-standing, hang over the road like normal traffic lights, and not be in the way of any vehicles. This was so that later on in testing, members of the lab could simulate different scenarios with the traffic lights at the intersections and test the vehicles’ interactions. Our design was extremely rudimentary, it just had the wires and board hanging out the back and we had to plug the boards into a source of power, but they did work, and we we’re able to sync up opposite lights on a timer system, which was a very good proof of concept. As with the VehiclesV3 project, I was not able to continue past the summer due to school, so this was all I was able to assist with.

I am beyond thankful for the time I was able to spend working in these amazing research labs. I am grateful to Dr. David L. Burris and Dr. Andreas Malikopoulos for trusting a high school student in their research labs, and to the various PhD, graduate, and undergraduate students who let the high school intern help them with their research after they took the time to explain it to me. I can’t begin to thank Mel Jurist of the UD K-12 program for allowing me the opportunity to be a part of this internship program, it set me ahead as a person and as an engineer. My time in these research labs made me into the engineer I am today and gave me experience in research labs that very few individuals my age have.